Terminated..But Seeking Relief: How to Calculate Front Pay

Posted May 31st, 2016.

Categories: Employment Law, The Calculating Lawyer.

Front pay is compensation for future wage loss that results from present employment-related circumstances. In most scenarios, it serves as a form of future wage-based restitution for victims of job discrimination. However, front pay is only available where reinstatement is not possible or appropriate. Thus, if a job has been filled or no longer exists, or if the employer-employee relationship has been so severely damaged that the relationship is unsalvageable, then front pay may be awarded as an item of damages.

In a Title VII employment discrimination case, one federal court has articulated nine factors to be considered in determining whether to award front pay to a successful plaintiff: (1) whether the employer is still in business, (2) whether there is a comparable position available for the employee to assume; (3) whether an innocent employee would be displaced by reinstatement; (4) whether the parties agree that reinstatement is a viable remedy; (5) whether the degree of hostility or an animosity between the parties – caused not only by the underlying offense but also by the litigation process – would undermine reinstatement; (6) whether reinstatement would arouse hostility in the workplace; (7) whether the employee has since acquired similar work; (8) whether the employee’s career goals have changed since the unlawful termination; and (9) whether the employee has the ability to return to work for the defendant employer – including consideration of the effect of the adverse employment action on the employee’s self-worth.

Therefore, before thinking about front pay, employment lawyers must think about the prospects of reinstatement for the aggrieved employee, and whether they are likely to recover front pay in a contested case.

In calculating front pay owed to a victim of employment discrimination, the following basic rules must be followed:

- There must be a start date (usually the date specified in a settlement or the date of a judgment).

- There must be an end date (based on work-life expectancy or other factors).

- There must be an adjustment for wages the employee could earn in the future using reasonable efforts.

Other adjustments may be warranted because of the particular character of the parties or the peculiar circumstances of a dispute. For example, a front pay award may be reduced by a factor that represents an employee’s uncertain future in a position (such as may be determined based on the employee’s declining health or a history of short-term employment and frequent job-hopping). The calculation of front pay may be adjusted to account for the availability of comparable employment opportunities and the time reasonably required for the employee to secure substitute employment. For older employees, it may also be adjusted to take into consideration the employee’s projected retirement age.

Front pay can also include projected promotions, bonuses, pay raises, and cost-of-living increases that the employee would have enjoyed had she not been terminated or forced to leave the job. However, proof of such enhancements will need to be gathered and produced in the form of admissible evidence before a court will infer that an employee would have earned greater amounts of compensation in the future.

A court considering an employment discrimination case may also apply other factors to substantiate the likelihood that an employee seeking front pay would likely have earned future wages with the same employer over a particular period of time. These may include, for example, the employee’s intention to remain with the employer until retirement, the length of time other employees typically hold such positions, the length of time persons in similar positions at other companies generally hold such positions, and the status of the current job market and industry

Calculating Front Pay

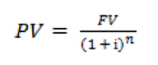

The basic unadjusted formula for front pay is essentially the same as the basic formula for loss of future earnings by personal injury lawyers. Since we know what the employee would have earned in future years (or at least we are proceeding on that assumption), our objective is to determine the present value (PV) of the future wage loss. We thus begin with the formula for present value:

where FV equals future value, i equals interest rate or discount rate, and n is the number of years.

where FV equals future value, i equals interest rate or discount rate, and n is the number of years.

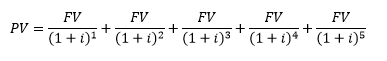

Assume that an employee would have earned exactly $100,000 for five more years, at which time he would have resigned or retired from employment. The question, unaffected by any adjustments or special considerations discussed above, is simply: what is the PV of $100,000 paid in each of five consecutive y ears? To answer this question, we must add the PV of $100,000 in year 1 to the PV of $100,000 in year 2, to the PV of $100,000 in year 3, and so forth until year 5. The formula is:

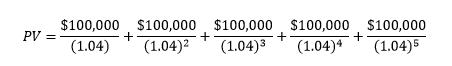

Let’s assume that the applicable discount rate (i) will be 4% (or .04) throughout the five-year period. Here’s the math:

PV = $95,153.85 + $92,455.62 + $488,899.64 + $85,480.42 + $82,192.71

PV = $444,182.24

So, assuming no other considerations, we can say that the discounted amount of future wage loss (that is, the front pay for the five-year period) would be $444,182.24.

We may wish to modify the numerator in each the fractions above if we could establish, for example, that the employee seeking front pay would have enjoyed certain increased wages after two years. The same would hold true if we has reason to believe that the employee’s income would decline at some point over the five years.

We may also wish to modify the denominator in the fractions above if we have reason to believe that interest rates (discount rates) would increase or decrease at some point during the five-year period. Growth rates and inflation rates may also offset our discount rate.

While this hypothetical assumes a five-year wage loss, other cases may suggest that the

aggrieved employee would have continued working for the employer for the rest of his life, or, more appropriately the rest of his working life. The cutoff date for front pay, however, cannot be arbitrarily pinned to a projected retirement age (such as 65 or 70). The more reliable approach is the LPE method, which considers the possibility that a particular individual will be living (L), that he will be participating (P) in the labor force, and that he will be actually employed (E). The product of these three probabilities, L x P x E, indicates an arguably more accurate statistic in determining work-life expectancy. (This will be the subject of a future blog). Notwithstanding this approach, many courts have expressed a reluctance to award front pay beyond 10 years.

In order for a front-pay formula to be accepted, it must therefore rationally adjust for the realities of the workplace, the logical progression of the employee’s work life, and other applicable factors. Consider, for example, an employee who has lost a job paying $100,000 per year, but has been able to find a new job paying $55,000 per year. Her front pay is thus reduced by her replacement pay, leaving her with a net annual loss in the future earnings of $45,000 per year. Let’s also assume that the employee’s employment history, pretrial testimony, and personal characteristics lead to the conclusion that she would have worked for the first employer for only four more years. Let’s also assume that earnings were expected to grow at 2% during the four-year span, and the interest rate was set at 4%. Here is how to proceed:

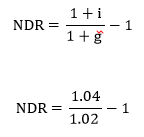

Step 1: Determine the net discount rate (NDR). The NDR is technically more accurate than a simple discount rate because it considers both the market interest rate and a growth rate. We might therefore say that the net discount rate is nothing more than the discount rate (or market interest rate) minus the growth rate. Thus, NDR = i – g, where “i” is the interest rate and ‘g” is the growth rate. In our hypothetical, the interest rte is 4% and the growth rate is 2%; therefore, NDR = 4 – 2, or 2%. The more accurate adjustment for NDR, however, comes from a slightly more complicated formula, which will produce a result close to 2%, but even more precise:

NDR = 1.01960 – 1

NDR = 0.01960%

NDR = 1.96%

Step 2: Determine the net wage loss per year. As noted above, if the employee was earning $100,000 at the first job, and now earns $55,000 at the second job, her net wage loss per year is $45,000.

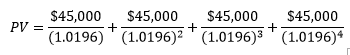

Step 3: Plot the formula by adding PVs for each year. Restate the PV value formula for each year in question. The numerators should state the amount of future net wage loss, and the denominators should state the NDR (1 + NDR). The NDR for each year is raised to the nth power, where “n” equals the year in question. The sum of each year’s PV calculation provides the PV for the entire four-year stream.

PV = $44,134.95 + $43,286.53 + $42,454.43 + $41,638.32

PV = $171,514.23

Therefore, the employee in this hypothetical case scenario would be entitled to front pay of $171,514.23.